I recently started writing an assembler from scratch using C++17 for a somewhat obscure operating system. The assembler’s design supports multiple target architectures, but for now, I only need to support the MIPS I instruction set, which happens to be extremely convenient, in that it’s trivial to encode.

A single MIPS assembler instruction is comprised of an operation mnemonic along with an optional operand list (e.g. addi $t1,$v0,0xFF). The proper machine encoding of the instruction (i.e. the layout of its 32 bits) is dictated by the instruction’s format type, which is documented for all MIPS I instructions in the IDT R30xx Family Software Reference Manual.

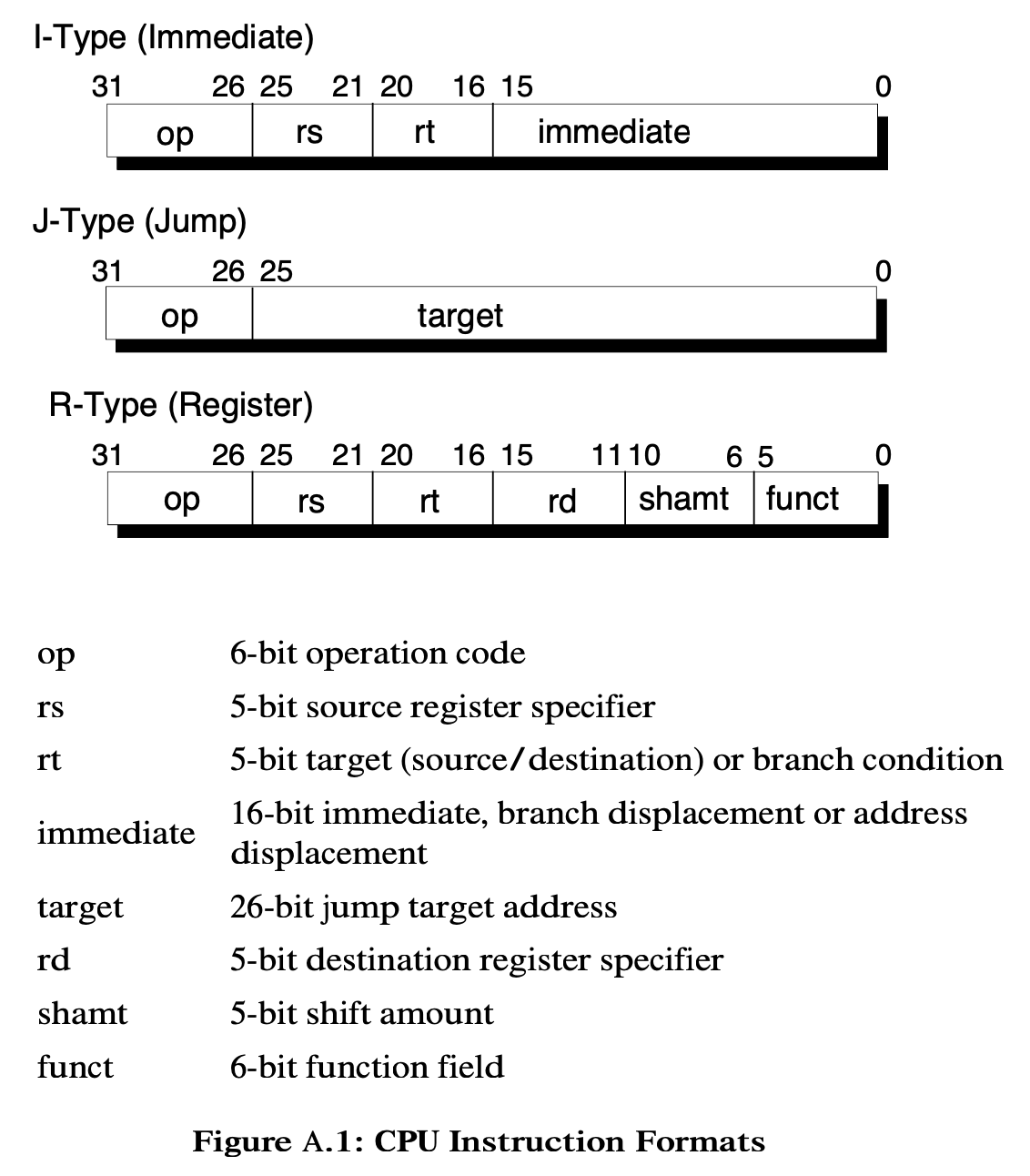

The three MIPS Instruction Encoding Formats

The figure (A.1) shows how the available 32 bits of an instruction are used by each of the three encoding formats.

From IDT R30xx Family Software Reference Manual

- Bit-fields

rs,rt, andrdencode the index of a CPU register (0 thru 31). - Bit-fields

immediate,target, andshamtencode a user-supplied numeric constant value. - Bit-fields

opandfunctencode an assembler-supplied numeric constant value (i.e. flags), used by the CPU to identify and configure itself for the instruction.

Declarative Instruction Encoding [C++17][constexpr if]

To keep all of the encoding rules in one place, the assembler supports the following declarative syntax:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef Instruction (*EncodeFunc)(const Entry&);

std::unordered_map<std::string, EncodeFunc> inst_encoders = {

{ "add", RType<0b000000, Arg, Arg, Arg, 0b00000, 0b100000, RTypeTuple<RD, RS, RT>> },

{ "addi", IType<0b001000, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeTuple<RT, RS, Immediate>> },

{ "beq", IType<0b000100, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeTuple<RS, RT, Immediate>> },

{ "bgez", IType<0b000001, Arg, 0b00001, Arg, ITypeTuple<RS, Immediate>> },

{ "bgezal", IType<0b000001, Arg, 0b10001, Arg, ITypeTuple<RS, Immediate>> },

{ "lw", IType<0b100011, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeOffset<RT, Immediate, RS>> },

// ... and many more!

}

Maps each instruction (by mnemonic) to a function which can properly encode it.

This map provides the encoding function for each and every MIPS I instruction. The expressions supplied for the map’s values generate these encoding functions via template expansion.

For example, from the snippet above, IType names a function template which accepts 5 template arguments:

- Opcode. Numeric constant expression (constant bits), only.

- RS. Constant bits, or a sentinel value Arg, which tells the function template to read the value from the user-supplied operands (5.).

- RT. Constant bits, or Arg.

- Immediate. Constant bits, or Arg.

- Operand parsing function. Reads the user-provided operands string into a tuple (more on this later).

Each function template (RType, IType, JType) instantiation results in the generation of a custom function which supplies the constant portions of the instruction’s encoding at compile-time. In other words, the bit-fields of the instruction that are always the same (used by the CPU to identify the operation it should perform) are passed into these function templates as integral constants (non-type integral template parameters). In theory, this should allow the compiler to combine all constant portions of the encoded instruction at compile-time.

The only deviation from this pattern occurs in the presence of the Arg sentinel, which uses a C++17 feature known as the constexpr if statement to provide special-casing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

template <uint32_t OpCode, uint32_t RS, uint32_t RT, uint32_t Immediate, ITypeSyntaxFunc Syntax>

Instruction IType(const Entry& entry) {

// ...

auto operands = Syntax(entry.operands.value_or(""));

if constexpr (IsArgSentinel(RS)) {

instruction.data.u32 |= ParseRegister(std::get<assembler::RS>(operands).value()) << 21U;

} else {

instruction.data.u32 |= RS << 21U;

}

// ...

}

Function template for MIPS I-type instructions.

Note that the function

IsArgSentinelisconstexpr.

The function template shown above (used for MIPS I-type instructions) uses a constexpr if statement to generate code to read the value for RS from the user-provided operand string (this is the operands list provided after the mnemonic), if and only if RS as specified by the template instantiation is the Arg sentinel.

A constexpr if statement tests the result of a constant expression (provided as its condition), and discards the statements of the branch not taken. This condition is evaluated at compile-time, making it possible for the compiler to exclude the failed branch from the function’s code.

If the value is true, then statement-false is discarded (if present), otherwise, statement-true is discarded. — cppreference.

Reading the Operand String [C++14]

The instruction function templates (i.e. IType, RType, JType) make no assumptions about the format of the operand string nor the ordering (or count!) of its contained operands.

Instead, each of these function templates accept a function pointer (5. from the example above) to an operand string parsing function, which splits the operand string into an std::tuple of the relevant fields for the instruction format.

The function templates can then simply use the type-based overload of std::get (C++14) to retrieve specific operands:

1

auto& rs_operand = std::get<assembler::RS>(operands);

This usage is shown in context for the I-type function template in the previous section.

Declarative Operand Parsing

To prepare these tuples, we must split an operand string into its components in accordance with the syntax rules of the corresponding assembler instruction.

The syntax rules for an instruction dictate:

- The formatting of the operand list. Either tuple-style (e.g.

$t0,$v0,0xFF) or offset-style (e.g.$t0,0xFF($v0)). - The ordering of the instruction components to which each operand will bind. For example, is

$t0,$v0,0xFFsupposed to beRT,RS,ImmediateorRS,RT,Immediate?

Both of these rules can be implemented declaratively using function templates as well (see ITypeTuple and ITypeOffset):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Add immediate uses tuple syntax: addi rt,rs,imm

{ "addi", IType<0b001000, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeTuple<RT, RS, Immediate>> },

// Branch equal uses tuple syntax: beq rs,rt,imm

{ "beq", IType<0b000100, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeTuple<RS, RT, Immediate>> },

// Load word uses offset syntax: lw rt,imm(rs)

{ "lw", IType<0b100011, Arg, Arg, Arg, ITypeOffset<RT, Immediate, RS>> },

MIPS I-type instructions with different operand string format requirements.

Notice in the above examples that the order of our template parameters (i.e. RS, RT, Immediate) defines the operand order for the instruction.

The implementation of this syntax relies heavily on the type-based overload of std::get, which allows us to bind the I-th operand from the operand string to whichever tuple field type was provided for the I-th template argument, in the resulting tuple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

// Define wrapper types for each I-type operand.

struct RS : std::optional<std::string> { using optional::optional; };

struct RT : std::optional<std::string> { using optional::optional; };

struct Immediate : std::optional<std::string> { using optional::optional; };

/* Reads a 3-tuple string format (e.g. "$t0,$v1,0x3") to a tuple of MIPS I-type operand info.

* The order of the operands in the string is specified using the type parameters.

*

* For example, ITypeTuple<RS, RT, Immediate>("$t0,$v1,0x3") tells us to read

* "$t0" as RS, "$v1" as RT, and "0x3" as Immediate.

*/

template<typename Arg1, typename Arg2, typename Arg3>

std::tuple<RS, RT, Immediate> ITypeTuple(std::string operand_str)

{

// Split operand string into fields (e.g. "$t0,$v1,0x3" => ["$t0", "$v1", "0x3"])

auto operands = Split(operand_str, std::regex(","));

// Create a new MIPS I-type tuple, with all fields initialized to std::nullopt.

auto tup = std::make_tuple<RS, RT, Immediate>(std::nullopt, std::nullopt, std::nullopt);

// Load tuple fields specified from this function's template args.

//

// This uses the type-based specialization of std::get, which retrieves a reference to the tuple member

// matching its type parameter (since C++14).

//

// https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/tuple/get

std::get<Arg1>(tup) = operands[0];

std::get<Arg2>(tup) = operands[1];

std::get<Arg3>(tup) = operands[2];

return tup;

}

ITypeTuple implementation for 3-tuple operand strings.

Optional Operands [C++17]

You may have noticed the use of std::optional (C++17) above. This type is used to represent a value which may or may not be present. All wrapper operand types extend std::optional:

1

struct RS : std::optional<std::string> { ... };

This allows them to be specified as std::nullopt by operand parsing functions for which not all operand types are applicable. For example, many I-type instructions allow only two user-specified operands:

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Example: bgez $t0,0xCF

//

// RS = $t0, Immediate = 0xCF// Field RT does NOT come from the operand list. It must always

// be 1, as required by the bgez reference spec.

{ "bgez", IType<0b000001, Arg, 1, Arg, ITypeTuple<RS, Immediate>> }

An ITypeTuple function template with two template arguments handles this case by filling only two of the three operand fields in the resulting tuple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

template<typename Arg1, typename Arg2>

std::tuple<RS, RT, Immediate> ITypeTuple(std::string operand_str) {

auto operands = Split(operand_str, std::regex(","));

auto tup = std::make_tuple<RS, RT, Immediate>(std::nullopt, std::nullopt, std::nullopt);

std::get<Arg1>(tup) = operands[0];

std::get<Arg2>(tup) = operands[1];

// Note that one of the fields will *always* be std::nullopt

return tup;

}

ITypeTuple implementation for 2-tuple operand strings.

The remaining field (not user-specifiable) will be std::nullopt (RT in the case of bgez), though it will never be read as such, since no code will be generated to read it in the corresponding IType function template instantiation.

It would have been possible to use variadic template arguments to handle both 2 and 3-tuples using a single function template, but this was decided against for simplicity.

Further Reading: constexpr Function Parameters

In this post, I mentioned the use of a sentinel value Arg used to special-case code generation for reading operands. Perhaps ideally, we could have used something type-safe (perhaps std::optional) as our non-type template argument’s type, but this is not possible in C++17.

To work around this limitation, a type template parameter can be used in conjunction with the newly introduced constexpr lambda (C++17).

Though this approach was not chosen due to complexity.

For a detailed explanation of this solution, check out Michael Park’s excellent blog post on constexpr function parameters”.

References

- IDT R30xx Family Software Reference Manual

- https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/language/if (if constexpr)

- https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/optional

- https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/tuple/get

- https://mpark.github.io/programming/2017/05/26/constexpr-function-parameters/

- http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21/docs/papers/2018/p0732r0.pdf